|

|

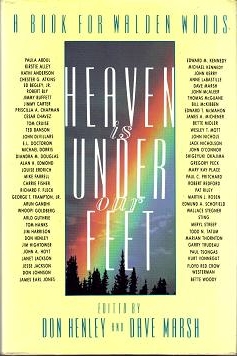

Heaven is Under Our Feet

FROM THE BIG CHILL TO THE BIG PICTURE

In 1982, I participated in a movie about a group of baby boomers who attend the funeral of a mutual friend who has committed suicide. During the course of the weekend together, they reflect on their lives and the loss of their sixties idealism. In The Big Chill, I played Meg, a single career woman who, after a disillusioning experience as a public defender, joins the corporate world as a real estate attorney. She jokes that her clients have gone from raping people to raping the land. Meg expresses a sense of loss from the bonds of their community of friendship and a sense of a shared commitment and goals.

Meg, and most members of the group, have either dropped out or sold out on their former idealistic values. Sam, a TV star, confesses his feeling of mistrust of people and Meg agrees that it's a "cold world out there. Sometimes I think I'm getting a little frosty myself." She seeks "warmth" from Nick and wants him to father her child. He is impotent since Vietnam and unable to comply. Sam, who is already a father, feels guilty about his lack of attention to his own child. He also declines Meg's offer of fatherhood. She wants nothing from the men, just their sperm. She will raise the child on her own.

Meg's frustration in finding a man hit a chord in many career women of my generation. I was constantly stopped on the street by women who related to that predicament, whose longing for intimacy and partnership was thwarted by the inability to find the "right" man. Meg thinks she might not even want a man any more, just a baby. By playing Meg, I was able to try on all of her emotions, processes and decisions. I wore them and lived in them for three months. They aroused disturbing feelings. Pretending to be Meg, I learned a lot about myself.

I became conscious of my own alienation. Like Meg, work had become my family. I had no time to pay attention to the nagging feeling of separation from some core that I couldn't articulate. Meg thought a baby would bring her the connection, the intimacy, the "heart" she missed in her life. I realized that I needed to discover my own path to wholeness. I intuited that for me, this missing element would have to come from within before I could share it with someone else, whether that was a man or a baby.

The emotions that erupted from playing Meg could not be ignored or “busied” away. Like it or not, my unconscious took this opportunity to speak to me. I began a descent into the dark, scary, mysterious depths of my being, not realizing it was the beginning of a journey toward finding a new sense of connection. I went from the outer-directed, work-centered, masculine journey, into the inner-directed, still waters of the feminine journey.

So why in the Sam Hill am I telling this story in a book about ecology? My experience, Meg’s “frostiness,” Nick’s impotence, Sam’s mistrust, a friend’s “burnout,” a neighbor’s heart disease, a couple’s divorce, the isolation of an elderly woman on the street, a newborn baby’s addiction to crack, a teenager’s bulimia, have become everyday occurrences. These are human examples of a culture that is in need of healing and transformation. Now a growing group of scholars and researchers are arguing that there are real connections between the diseases in us and our society, and the host of environmental tragedies that are ravaging our earth.

In her book, A Passion for This Earth, Valerie Andrews writes about the eighteenth century philosopher, Leibnitz, and his book, The Monadology. In it he said that the whole of his life is reflected in the smallest unit of reality or, in our context, what is happening among individuals is happening societally and to the entire planet.

The effects on the planet may not be quite as easy to see as personal problems in our daily lives, but they’re there, and getting worse. Thomas Berry writes in The Dream of the Earth, “our entire society is caught in a closed cycle of production and consumption that can go on until the natural resources are exhausted or until the poisons inserted into the environment are fed back into the system.” We are making the land and air and sea so toxic that the very conditions of life are being destroyed. Due to our abuse of the planet, hundreds of thousands of species will be extinguished before the end of the century. This scenario is so unthinkable that, as Berry suggest, “a disturbance exists…on a greater order of magnitude than we dare admit to ourselves or even think about.”

How did we get in this state of dis-ease? In our race for power, control, position, more, better, newer, faster, our culture has worked itself into an all-consuming, undisciplined, and out-of-sync existence.

In The Chalice and the Blade, Riane Eisler describes two basic models of society: the dominator model (patriarchy or matriarchy), which ranks one half of the population over the other, and the partnership model, which involves the principle of linking rather than ranking, where diversity is celebrated and people aren’t broken down into inferior or superior groups.

Recent anthropological studies suggest that the partnership model is not just a theory, but has a basis in history. Marijua Gimbutas, in The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe, gives evidence of a matricentric society between circa 7000 and 3500 B.C. It was an earth-centered, agricultural, highly artistic and creative, Goddess-worshiping, egalitarian male-female society. Then came the Aryan invasions, and along with them a patriarchal model of social organization. This system was based on male dominance, male violence, and a generally hierarchic and authoritarian social structure. Four patriarchal structures have dominated Western history over the centuries: the classical empires, the religious establishment, the nation-state, and now the modern corporation. In all of these structures, males have dominated through systems based on power, control, and methods of warfare.

The dominator model is now deeply embedded in our cultural traditions, in our religious traditions, in our language, in our entire value system, and its negative effects are accelerating. Berry, Eisler, and many others suggest we must move toward a more encompassing, holistic mode of existence. We must move toward a partnership society, and that means including the feminine values that were once part of our culture—feminine values which, while largely ignored, remain an important part of our collective unconscious.

When I’ve mentioned this concept of balancing the masculine with the feminine, I’ve noticed resistance from some of my men friends. The hair goes up on the back of their necks—oh no, some feminist rap. This is not another divisive concept, but an inclusive one. Masculine forces have been at work in our culture to the exclusion of a counterbalanced feminine force. These archetypal forces are creative, and men and women contain both the masculine and the feminine. But there is much evidence that the predominance of masculine forces has become counterproductive—life-taking rather than life-giving—and needs to be balanced by the nourishing, nurturing energy of the feminine.

This does not mean that men should become like women, but that the whole culture, men and women, should begin to appreciate and discover values that are more intuitive, relational, and interdependent. In The Heroine’s Journey, Maureen Murdock writes, “we need the moist, juicy, green, caring feminine to heal the wounded, dry, brittle, overextended masculine in our culture.” We all share the blame for what has happened to our planet and must work together in partnership to reach a new way of being.

In moving toward partnership ways of being, as both men and women, we also need to discover our own authentic voices. We need to learn to form relationships with our unconscious, to “hear” the inner wisdom and guidance it can offer. Our bodies are conduits for this information, but through excessive food, alcohol, drugs, sex, and busyness we numb our bodies, and its signals are unable to reach our consciousness.

I have learned that my “gut alarms” are powerful signs and when I ignore them, trouble is sure to follow. As I become more in tune with my body, I am increasingly grateful for its guidance. But I have to remember to be still and slow down so that I can “feel” its messages. When I get caught in the busy, doing, linear, rational mode, I begin to feel split apart, off-track, disconnected. I know I need periods of solitude, gardening and hiking in nature. Meditation and prayer also help me reconnect to my body and to a spiritual Source, the Self deep within. Being present in this realm has proven to be a comforting and nurturing experience, but alas, in depressions and burnout, it can also be frightening entering the unknown, where all seems to be arid and desertlike, devoid of meaning.

Experience has taught me, however, that hanging on through the darkness (and it has not been easy) pays off. In the darkness lie seeds of renewal and rebirth. I have learned the importance of patience and process, two values that are not appreciated or respected in our fast food, instant-gratification culture. I have a new understanding of faith and trust. I have begun to see that the rhythms and cycles of nature are a part of not only my personal rhythms but of all living creations on this earth. There is reciprocity and interdependence linking all living things. And while I continue to struggle on the inner path, I also experience a yearning to move beyond myself into the community for connection and relationship.

But this partnership business is not easy. Just think about the state of man-woman relationships. So often we are split apart by addiction, codependency, poverty, success, fear, illness, emotional unavailability, projections, alienation, and the inability to communicate. So how do we get together? What is the key? I wish I knew. But in my efforts, which range from the insane to the ridiculous, from the unconscious to the more conscious, I have learned a few things about what does not work. Seeking fulfillment or wholeness from a mate is impossible. Ultimately, he can not and will not fill the black hole. This is my responsibility. And we’re in trouble if I try to be his mother or he tries to be my father.

Some experts suggest that by taking the inner journey and coming into relationship with our inner, opposite, archetypal masculine and feminine forces that unconsciously drive our actions, we are less likely to project those forces onto our mates. Others say we need to discover and heal the secret wounds of childhood, so we will not act out and repeat the dysfunctional family dynamics in our adult relationships. New hope comes from acknowledging, grieving over, and accepting all the denied hurts and fears, and finally forgiving those that delivered them.

If I have the courage to look at my shadow side and acknowledge all the ugly, horrible, negative parts of myself that I have denied and driven into my unconscious and accept them, then their power over me begins to fade. When I begin to accept, with love, all the negatives in myself, I am more willing to accept the parts I’d like to criticize in my mate. In discovering who I truly am, I am more capable of allowing my mate to be who he truly is. The more my authentic self emerges, the more a healthy relationship is possible—based not on dominion or control of one over the other, but on a partnership of equals with diverse gifts, perceptions, and abilities. And getting back to Leibnitz’s theory, it follows that as we learn to accept the diversity in our own partners, our children and families, we also can celebrate the diversity of our neighbors—whether they live across the yard, the tracks, the state, or the world.

So by finding our authentic voices, we find the freedom to change the focus from self to others. And we respond to the need to serve a larger purpose. In community and partnership we can begin the difficult task of effecting change for our culture and our planet. And in spite of the enormous magnitude of our challenge there is hope.

There is hope in the growing ecology movement, where the focus is moving from our human-centered reality to nature-centered reality.

There is hope in our increased consciousness and awareness of what we have to do to heal ourselves, our community, and our planet.

There is hope in moving toward a partnership society and the feminine, eliminating the warfare system.

There is hope in reconnecting to the earth and becoming its lover again. But we can not love what we do not know. We must spend time with nature and experience the mystery of her rhythms and cycles of birth, death, and rebirth. We must teach our children to respect these mysteries and to have reverence for the sanctity of the earth, as our Native American people have always known.

There is hope in listening to the earth. We must come into communion with Mother Earth and rediscover her life-giving energies. Like the wisdom of our bodies, the body of the earth can aid and direct us in our mutual, interdependent journey back to wholeness. In the depth of her wounds lie the seeds of healing. We must let go of the illusion that we know what is best for earth. Our greatest hope is in forming a partnership with the earth, letting the earth become our guide.

I would like to acknowledge the following authors whose scholarships, research and insights informed this article:

The Heroine’s Journey, by Maureen Murdock (Shambhala Publications, 1990)

The Dream of the Earth, by Thomas Berry (Sierra Club Books, 1988)

The Chalice and the Blade, by Riane Eisler (Harper and Row, 1987)

Fire in the Belly, by Sam Keen (Bantam Books, 1991)

“Not till we are lost, in other words, not till we have lost the world, do we begin to find ourselves, and realize where we are and the infinite extent of our relations.”

Walden

Henry David Thoreau

........................................................................................................................

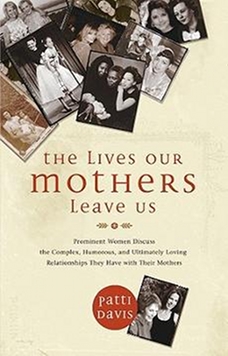

The Lives Our Mothers Leave Us

MARY KAY PLACE

When Mary Kay Place says, “It never occurred to me my mother wouldn’t be there for me,” it’s not clear at first if she’s referring to the past or the present. Gwendolyn Lucille Place died in 2003 of complications related to Alzheimer’s.

With the death of a parent, there is an unfamiliar emptiness—a persistent feeling that he or she is still just a phone call away. But Alzheimer’s compounds the ache, because the journey of loss begins years before death has the final word. With every passing month and year, with every visit, the person you once knew has faded some more; all you can do is remember who they once were.

That is probably hovering somewhere behind Mary Kay’s comment, but she’s actually referring to her childhood. The Place home was lively, warm—occasionally tumultuous, but always grounded in love. Mary Kay is the middle child, the only girl sandwiched between two brothers, and none of them ever doubted their parents were absolutely devoted to them.

. . .

Gwendolyn Lucile, whom everyone called Gwen, married her college sweetheart in Texas just before World War II. It was a time when many young men said goodbye to their new brides and traveled across the ocean, not knowing if they would return in one piece, or at all. By the time Mary Kay’s father joined the Marines and sailed off to fight in the war, Gwendolyn was pregnant with her first child. A war bride living in Port Arthur, Texas, she became a schoolteacher—a career she would set aside once her husband returned from the war, but would take up again when Mary Kay was a sophomore in high school.

“She was a good teacher,” Mary Kay says. “She would take kids who caused trouble in other classes and give them special attention. She’d make them class monitor, or somehow show trust and interest in them when no one else had. But then she’d say to them, ‘You have to live up to this responsibility. No more bad behavior—I’m counting on you.’ When my mom died, we got letters from a lot of her former students. One wrote that my mother inspired her to become a teacher even though she’d spent a lot of recess periods writing 100 times: ‘I will not talk in class.’”

By the time Mary Kay was born, the family had moved to Tulsa, Oklahoma, and five years later her younger brother was born. Gwen settled into the life of a typical ‘50’s homemaker; she was a homeroom mother, a Camp Fire leader, a Little League volunteer.

“She was very involved in our lives,” Mary Kay says. “We knew we could always count on her, but we also knew that if we got into trouble, we’d have to take responsibility for our actions. She was never one to deny the truth about her children or sugarcoat things. She got that attitude from her parents, who were very pragmatic, pull-yourself-up-by-the-bootstraps people. They didn’t believe in feeling sorry for yourself, and neither did my mother. Mainly, it was a matter of choosing to focus on the positive.”

Gwen’s relationship with her husband was a bit more complicated.

“At first glance, my parents had a traditional postwar marriage. My father was head of the household and a college professor, with a big, outgoing personality and community recognition. He was the star, and Mom was the supporting player. But where it counted, they were equal partners. She always spoke her mind, and since they both had strong personalities, they argued a lot—it was just their way.

“Once when we were kids, the whole family was traveling in the car to my grandparents’ home in Texas, and Daddy was in a hurry to get there. He was cranky and kept passing one country diner after another, saying it didn’t look right or didn’t seem clean enough. Finally, he agreed to stop at some dinky store. Mother went in and bought groceries so we could eat in the car and keep going. While she was struggling to make sandwiches in her lap, Daddy was on a roll—telling her to be careful with the mayo on the car’s seat, don’t let the tomato drip…he was going on and on. Finally she said, ‘One more word and I’m throwing this out.’

“Well, he couldn’t resist a few more comments; and sure enough, down went the window and out went the bread, the mayonnaise, the potato salad, lettuce, tomatoes—all of it. My brothers and I looked at our lunch on the highway behind us, stunned.

“But Daddy got the point—we stopped at the next restaurant. For my parents, arguing was just blowing off steam, a way to work things out. Flare-ups were over as quickly as they started, and they didn’t hold on to any anger. Once it was done, it was as if it had never happened.”

We are imprinted as children in many ways, and Mary Kay just assumed that every home was like hers. Later, when she was grown and entering into her own relationships, she found herself following the same pattern she’d grown up with—declaring her feelings, even anger, and expecting the other person to go toe-to-toe with her. She would then expect the whole dustup to be over and forgotten.

Laughing, she says, “Of course it doesn’t always work like that. I’ve definitely freaked out a few people.”

Some of the most enduring lessons Mary Kay learned from her mother had to do with empathy and compassion. She recalls coming home one day after school and telling her mother that she’d made plans with a friend but had then gotten a more enticing offer, one that she wanted to take.

“Well, how do you think you’d feel if someone did that to you?” her mother asked. “Put yourself in her shoes.”

Another lesson had to do with treating people equally, not making distinctions. Mary Kay didn’t know, growing up, that there was such a thing as cattiness between women. She didn’t know because her mother had never demonstrated it. Gwen genuinely liked both men and women, never gossiping or talking behind anyone’s back. As quaint as it seems, Gwen would tell her children with complete earnestness, “If you can’t say something nice, don’t say anything at all.”

“She wasn’t a saint, though,” Mary Kay points out. “She could be dogmatic, bossy, and stubborn as a mule.”

But she was also down-to-earth and “a whole lot of fun.”

Gwen’s pep talks were a combination of “common sense, enthusiasm for your hopes and dreams, and an absolute belief that you could do anything you put your mind to.” Today, if Mary Kay is facing a challenge, she still hears her mother’s voice in her head, spurring her on and encouraging her.

. . .

The best teachers are those who know when to be students. When Mary Kay found herself paralyzed by clinical depression, Gwen would learn a profound lesson—that sometimes life drags you beneath the surface into dark waters; and all you can do is float, look around, search within, and try to understand how you got there…until light breaks through and you can start swimming again.

It was the ‘80’s, and Mary Kay had done more than 300 episodes of “Mary Hartman,” as well as films and albums—all without a break. She was burned-out. “I wouldn’t slow down, so my body did it for me. I just crashed. It was like the bottom had fallen out. Even though I was trying to get a handle on it with therapy, I couldn’t pull myself out of that dark place.”

Gwen realized that her daughter’s situation wasn’t going to be alleviated by the usual “pulling oneself up by the bootstraps” philosophy. Depression renders its victims helpless.

“Mother didn’t understand it at first,” Mary Kay says. “No one in my family had any experience with something like that.”

Knowing she had to rescue her daughter, Gwen flew to Los Angeles from Tulsa, stayed with Mary Kay, and was there for her in every way possible. After a couple of weeks, a moment came that would ultimately transport mother and daughter back into life as they had once known it, although both would return wiser for the experience.

“Toward the end of her visit, I made some kind of defeatist comment, and she gave me a look. Something clicked in her eyes. She never said a word, but I got her message: ‘It’s time for you to climb out of this. You’ve got to try harder. I know you can do it. You will do it, and you’ve got to start now.’ And I did. That was the turning point.”

Sadly, Gwen couldn’t rescue herself from Alzheimer’s. Because her own mother had been stricken with the disease, she did know that she was at risk. She started to notice small symptoms a year before retiring from teaching.

“Early on, she began taking the drug Aricept, which did manage to keep her in a holding pattern. Then after Daddy retired, the two of them spent the next 14 years traveling, entertaining friends and family, and basically enjoying their lives. Except for my father, no one else in the family knew about Mother’s diagnosis for a long time.”

But Alzheimer’s is a relentless thief, and its conquest is inevitable. Eventually, as Gwen’s symptoms became more obvious, everyone learned the truth.

“But even then,” Mary Kay says, “Mother carried on just like she always had. She’d had her checkbook to the cashier at the grocery store and say, ‘I have Alzheimer’s. Can you fill out my check? I’ll sign it.’ Her acceptance of what was happening to her always amazed me. I’m sure she went through sadness and grief in private, but in front of us she just soldiered on, making the best of a situation she had no control over. Just like she always had.”

It was one of Gwen’s final lessons—that despite everything Alzheimer’s steals from a person, it can’t touch the spirit.

. . .

So what parts of Gwen live in Mary Kay? Not surprisingly, a strong sense of survival and determination, and a bit of the teacher as well…

“Her empathy and her practice of looking at a situation from another person’s point of view has not only helped me in life, but it’s helped me develop and understand the characters in my work. And when I’m directing, I can sometimes hear my mother’s voice in mine. I also share her temper when something makes me mad or I feel there’s an injustice.

“When the women’s movement encouraged us to find our voice, I realized how much my mother had provided an early example of that. I don’t shrink from conflict if that’s what’s in front of me. I can express myself, and I’ve learned to say no. And yes, I can be a bit bossy and stubborn at times.” She laughs and wags her finger in the air. “And then there’s the finger wagging. My mother did it when she wanted to make a point, and I often catch myself doing it. I once had a boyfriend who said to me, ‘What is that thing? Put that gun away.’”

. . .

One of the gifts of Gwendolyn Lucile Place’s life is that she lives on inside many people—not only her children, but the students she taught, the people who benefited from her wisdom and compassion, and the visitors who stayed longer than they intended to simply because it felt good to be around her. Some people are born to be teachers; and those who are lucky enough to cross their paths linger a while, learn, and are changed forever.

. . .

Back to The Mary Kay Place Place |